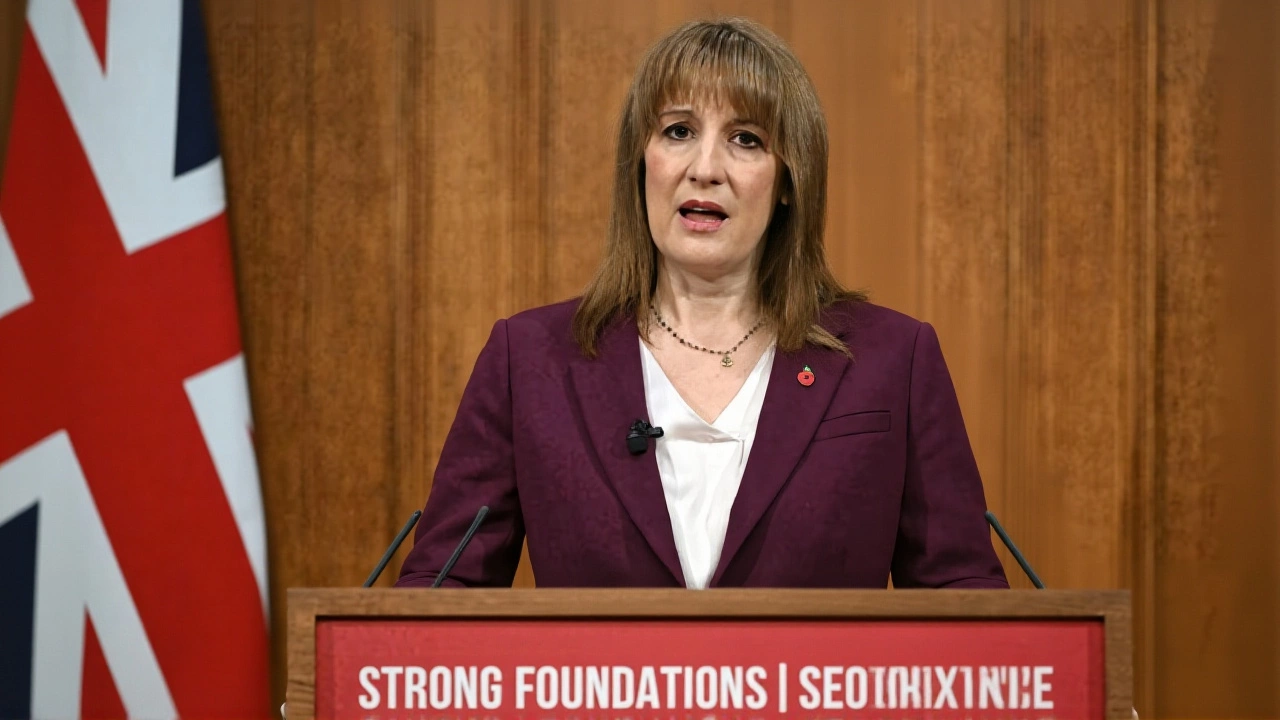

On Wednesday, November 26, 2025, Rachel Reeves, Chancellor of the Exchequer, stunned Parliament with a budget that quietly reshaped Britain’s fiscal landscape — not with bold rate hikes, but with a cascade of hidden tax increases that will push the UK’s tax burden to a record 38% of GDP by 2031. Announced in the House of Commons, London, the Autumn Budget 2025 avoids the politically toxic move of raising income tax rates — the first such freeze since 1975 — and instead leans hard on fiscal drag, property levies, and asset taxation to plug a £22 billion hole in the public finances.

‘Quieter’ Tax Rises, Heavier Burden

Reeves, formally styled as The Right Honourable Rachel Jane Reeves, MP, made it clear: she wouldn’t raise the basic, higher, or additional rate of income tax. But she didn’t need to. By freezing income tax thresholds until April 2031 — and letting inflation push more earners into higher bands — the government is effectively raising taxes on millions without changing a single percentage point. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates this alone will generate £11.4 billion annually by 2030, as workers earning £35,000 today find themselves paying higher rates by 2028 simply because their pay rose with inflation.‘It’s not a tax rise on paper,’ said Gary Mackley-Smith, a tax advisor at Bishop Fleming. ‘But for a teacher in Leeds or a nurse in Manchester, it feels just like one. Their pay went up 4%, their tax bill went up 6%. That’s fiscal drag with teeth.’

The Mansion Tax That Broke the Mold

The most visible — and controversial — measure is the High Value Council Tax Surcharge, a new levy targeting properties worth over £2 million. Owners of homes valued at £2 million to £5 million will pay an extra £2,500 annually. Those with properties over £5 million? £7,500. The justification? ‘The average Band D family home pays more in Council Tax than a £10 million property in Westminster,’ reads the official Autumn Budget 2025 document. The policy targets 40,000 homes nationwide, mostly in London, Surrey, and Oxfordshire. Critics call it punitive; supporters say it corrects a decades-old imbalance.But here’s the twist: the surcharge isn’t replacing existing Council Tax. It’s layered on top. So a £6 million property in Kensington might now pay £18,000 in Council Tax plus £7,500 in surcharge — nearly £26,000 a year. That’s more than most families pay in income tax.

Wealth, Not Work: Taxing Assets

The budget shifts focus from taxing wages to taxing wealth. Dividend allowances are being cut. Savings interest thresholds are tightening. The capital gains tax exemption for Employee Ownership Trusts — once a £2 billion liability — has been slashed from 100% to 50%. The move, the Treasury says, is to ‘restore fairness’ between those who earn through work and those who earn through assets.‘Income from savings and property faces no equivalent of National Insurance,’ the Budget document states. ‘That gap is being closed.’ The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), a respected London-based think tank, called the approach ‘prudent’ — though not popular. ‘In the face of a small deficit, Rachel Reeves chose to raise taxes. In part, this was to increase her “headroom” to £22 billion,’ noted IFS director Paul Johnson in an early analysis. ‘It’s not the most exciting strategy, but it’s the least destabilizing.’

Other Measures: From EVs to Pensions

The budget is a laundry list of targeted levies:- eVED: A new Electric Vehicle Excise Duty kicks in from 2027, replacing lost fuel duty revenue as petrol cars vanish.

- Inheritance tax thresholds: Frozen until 2030/31, projected to bring in £14.5 billion annually as rising house prices drag more estates into taxation.

- Travel to work tax breaks: The Cycle to Work scheme’s tax exemption is being capped at £1,000 per year.

- Overseas pensioners: No more cheap access to UK state pensions for those who’ve lived abroad for over 10 years.

- Benefit cap lifted: The two-child limit on universal credit is removed — funded by the above measures.

- National living wage: Rises to £12.71 per hour from April 2026, adding pressure to small businesses already reeling from last year’s National Insurance hike.

‘It’s a veritable mixture of measures to add more complexity to the tax system,’ said Mackley-Smith. ‘You need a spreadsheet just to calculate your liability now.’

What’s Next? The Slow Burn

The full impact won’t be felt overnight. Fuel duty remains frozen until April 2026. The inheritance tax freeze ends in 2030. The mansion tax starts in April 2026. But the cumulative effect? By 2031, nearly every working household will be paying more in taxes than they did in 2025 — even if their income hasn’t changed.‘This isn’t a crisis budget,’ said economist Dr. Lena Kaur of the Centre for Economic Performance. ‘It’s a consolidation budget. Reeves is betting that voters will tolerate higher taxes if they see public services improving — and if the burden falls on the wealthy, not the working class.’

But the wealthy aren’t the only ones feeling it. Pensioners who moved abroad are now locked out of their state pensions. Small businesses face new costs from the wage hike. Even electric car owners, once hailed as climate heroes, are now being taxed to fund the transition.

Why This Matters

The Autumn Budget 2025 marks a turning point. For decades, UK governments avoided taxing wealth directly. Now, Reeves has forced the issue. The message is clear: if you own assets, you pay more. If you earn wages, you pay more too — just slower, through inflation. And if you’re on benefits? You get relief, but only because someone else is paying for it.The real test? Will this strategy stabilize the economy — or deepen resentment? The OBR warns that public trust in the tax system is already at a 20-year low. Reeves gambled that fairness, not popularity, would win the day.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the mansion tax affect homeowners outside London?

While the mansion tax primarily targets high-value properties in London and the South East, it also affects 12% of homes in Surrey, 8% in Oxfordshire, and even a handful in rural areas like Cheshire and Hampshire where property prices have surged. A £2.3 million farmhouse in the Cotswolds would now pay £2,500 extra annually — a burden that could force some owners to sell or rent out rooms. The government estimates only 40,000 homes nationwide are affected, but the psychological impact is nationwide.

Why freeze income tax thresholds instead of raising rates?

Freezing thresholds is politically safer than raising rates. Since 1975, no chancellor has increased income tax bands without backlash. By letting inflation push earners into higher brackets, Reeves avoids the headline-grabbing ‘tax hike’ label while still raising £11.4 billion a year by 2030. It’s a stealth tax — invisible on paper, felt at the checkout.

Who benefits from the removal of the two-child benefit cap?

Around 220,000 families — mostly single-parent households and low-income workers — will gain an average of £1,800 annually. The policy, funded by wealth taxes and pension changes, aims to reduce child poverty. But critics warn it could disincentivize work if not paired with childcare support. The government says it’s part of a broader ‘fairness agenda’ — lifting the cap while taxing the wealthy to pay for it.

What’s the long-term impact on the economy?

The OBR forecasts GDP growth will remain below 1% through 2028 as higher taxes dampen consumer spending and business investment. But public debt as a share of GDP is expected to fall from 98% to 91% by 2031. The trade-off? Slower growth for greater fiscal stability. Economists are divided: some call it prudent consolidation; others warn it risks a ‘low-growth trap’ if productivity doesn’t improve.

Will this lead to tax avoidance or emigration?

The Treasury expects some high-net-worth individuals to relocate — especially with the pension access changes. But the UK’s property market is still one of the world’s most attractive, and the mansion tax only applies to UK-based assets. The government estimates only 1,200 wealthy individuals may leave over the next decade — a drop in the ocean compared to the £14.5 billion in inheritance tax revenue expected annually by 2030.

How does this compare to past budgets?

The 38% tax-to-GDP ratio is the highest since records began in 1948, surpassing even the 1970s peak of 37.2%. Unlike Labour’s 2007 tax hikes, which targeted top earners, this budget spreads the burden across wealth, property, and savings. It’s more like the 1981 Thatcher budget — but in reverse. Where Thatcher cut taxes to spur growth, Reeves raises them to stabilize the state. The strategy is ideological as much as economic.